CEOs today face more pressure to perform quickly and more scrutiny from boards and shareholders when performance lags. The cost of CEO failure is high in missed opportunity, poor employee morale, lost customers and poor shareholder returns. Quantifying the costs of poor CEO performance, PwC estimated that forced CEO turnover globally costs shareholders $112 billion in total returns annually.

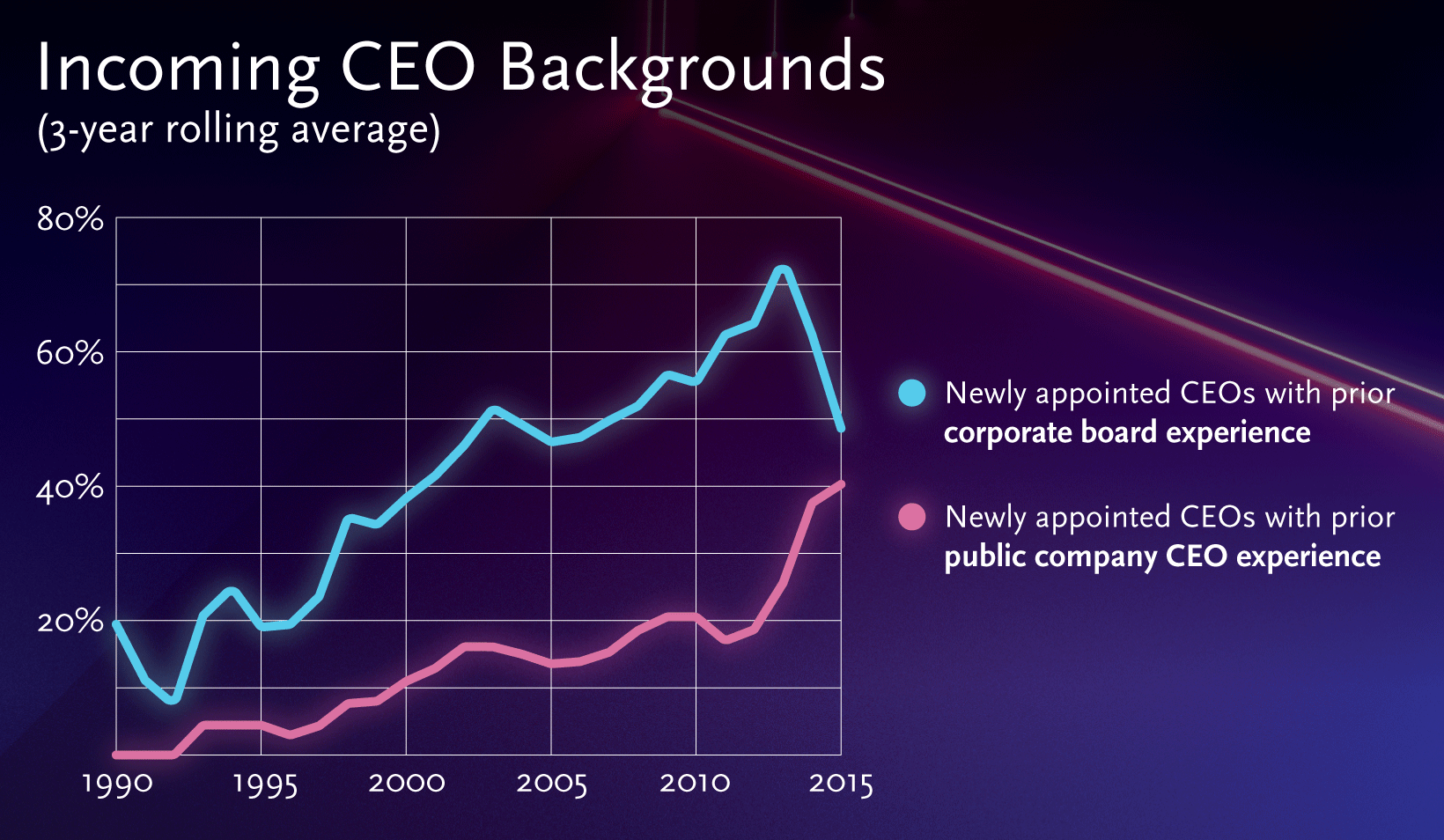

As the stakes for CEO success have increased, we find a growing preference in our CEO search and succession work for prior board or CEO experience as selection criteria. New research confirms these observations from our client work. We analyzed the backgrounds, tenure and performance of 736 S&P 500 company CEOs who left office between 2004-2017. Before the 1990s, few CEOs had previously served as a public company CEO before moving into the role. That started changing in the mid-1990s, when the number of CEOs with prior CEO experience began to increase steadily. By 2015, 40 percent of the CEOs in our S&P 500 data set had prior CEO experience. In the same time frame, the number of new CEOs with prior public company board experience increased from less than 20 percent to more than 70 percent at its high.

Common sense suggests that more experience is better, but is it? While boards appear to be showing a growing preference for these backgrounds, our study found no discernable link between prior board or CEO experience and greater total shareholder return (TSR). If value creation is not driving this trend, what is? Several developments — both on the supply and demand sides — help explain this phenomenon.

Changing board composition. Board demographics have changed dramatically in the past 20 years, particularly after the passage of the Sarbanes-Oxley Act (SOX) in 2002, increasing the supply of senior executives with board experience. As both the CEO job and board service grew more challenging, CEOs accepted fewer outside corporate board roles. Boards broadened their recruiting profiles in response to this shift and other demands (e.g., the desire to increase diversity in the boardroom or the need to add digitally savvy executives to the board).

Changing board composition. Board demographics have changed dramatically in the past 20 years, particularly after the passage of the Sarbanes-Oxley Act (SOX) in 2002, increasing the supply of senior executives with board experience. As both the CEO job and board service grew more challenging, CEOs accepted fewer outside corporate board roles. Boards broadened their recruiting profiles in response to this shift and other demands (e.g., the desire to increase diversity in the boardroom or the need to add digitally savvy executives to the board).

With CEOs opting out — the percentage of new S&P 500 directors who were sitting CEOs fell from 53 percent to 19 percent between 2000 and 2018 — retired CEOs partially filled the void. Most of the remaining gap was filled with active and retired C-level executives. This group accounted for just 6 percent of new S&P 500 directors in 2000 versus 21 percent in 2018. Because board service is often seen as a valuable development experience for aspiring CEOs, many senior executives view board seats as an important career step.

Changing perceptions about CEO longevity. Many boards are thinking differently about structuring the CEO role. For example, some boards may consider hiring CEOs for specific “chapters” or business needs, rather than viewing every CEO in terms of long-term legacy-building. Similarly, directors today are more comfortable with CEOs serving beyond age 65, for example, assuming a 60-year-old could serve seven or eight years as CEO.

Changing perceptions about CEO longevity. Many boards are thinking differently about structuring the CEO role. For example, some boards may consider hiring CEOs for specific “chapters” or business needs, rather than viewing every CEO in terms of long-term legacy-building. Similarly, directors today are more comfortable with CEOs serving beyond age 65, for example, assuming a 60-year-old could serve seven or eight years as CEO.

Hitting the ground running. To supplement our research, we surveyed 48 experienced directors to better understand their views about the value of prior experience in CEOs. Nearly two-thirds (65 percent) agreed that prior CEO experience is valuable or extremely valuable, and 52 percent said the same about prior board experience. Directors viewed these backgrounds as providing new CEOs with a head start in areas such as communication with the board, governance perspective, pattern recognition, exposure to other functions and industries, and managing risk.

Hitting the ground running. To supplement our research, we surveyed 48 experienced directors to better understand their views about the value of prior experience in CEOs. Nearly two-thirds (65 percent) agreed that prior CEO experience is valuable or extremely valuable, and 52 percent said the same about prior board experience. Directors viewed these backgrounds as providing new CEOs with a head start in areas such as communication with the board, governance perspective, pattern recognition, exposure to other functions and industries, and managing risk.

A safer bet. It’s widely recognized among directors that there is a wide gap between the CEO and executives even one level down in the scope of the job and the required skill set. While most directors responding to our survey equated experience more closely with value creation, others viewed prior CEO experience as a factor in minimizing the risk of failure. This is hardly surprising given our human tendency to assume that someone untested in a role is more likely to fail than someone who has done it before, especially when a new role represents such a significant leap. And, given the pressure from activist investors, directors can be sensitive not only to performance risk — the possibility that someone without prior experience could fail — but also reputational risk — the potential for a negative market reaction to the hiring of an unknown and untested leader. This is one reason executives who have already built credibility and a strong reputation in the investment community are highly prized.

A safer bet. It’s widely recognized among directors that there is a wide gap between the CEO and executives even one level down in the scope of the job and the required skill set. While most directors responding to our survey equated experience more closely with value creation, others viewed prior CEO experience as a factor in minimizing the risk of failure. This is hardly surprising given our human tendency to assume that someone untested in a role is more likely to fail than someone who has done it before, especially when a new role represents such a significant leap. And, given the pressure from activist investors, directors can be sensitive not only to performance risk — the possibility that someone without prior experience could fail — but also reputational risk — the potential for a negative market reaction to the hiring of an unknown and untested leader. This is one reason executives who have already built credibility and a strong reputation in the investment community are highly prized.

Assumptions about value creation. We found a strong correlation between directors who considered prior experience valuable and their belief that prior experience is important for increasing shareholder value. Directors who value these backgrounds — especially prior CEO experience — do so in large part because they view a past track record of value creation as predictive of future value creation. Directors express similar views in our work with clients. Boards that articulate a preference for prior CEO experience, especially in companies that are struggling, want candidates who can “hit the ground running.” They expect that experienced CEOs will require less on-the-job learning: CEOs who have “done it before” should be able to quickly evaluate the situation and understand the levers to pull to make meaningful short-term and long-term change. The fact that we see no difference in value creation between CEOs with these backgrounds and first-time CEOs suggests that boards may be undervaluing potential.

Assumptions about value creation. We found a strong correlation between directors who considered prior experience valuable and their belief that prior experience is important for increasing shareholder value. Directors who value these backgrounds — especially prior CEO experience — do so in large part because they view a past track record of value creation as predictive of future value creation. Directors express similar views in our work with clients. Boards that articulate a preference for prior CEO experience, especially in companies that are struggling, want candidates who can “hit the ground running.” They expect that experienced CEOs will require less on-the-job learning: CEOs who have “done it before” should be able to quickly evaluate the situation and understand the levers to pull to make meaningful short-term and long-term change. The fact that we see no difference in value creation between CEOs with these backgrounds and first-time CEOs suggests that boards may be undervaluing potential.

Understanding when experience matters

CEOs who have “been there, done that” don’t necessarily create more shareholder value, our research shows. So, when considering CEO candidates with prior CEO or board experience, it’s important to do the following:

Consider the context. Success in one situation does not necessarily translate into success in another context. That’s why it’s important for boards to look deeper into CEO candidates’ experience to understand how the circumstances in which they were successful correlate to what is needed in the current situation. The objectives for the role — whether the CEO needs to lead a turnaround, for example — represent just part of the context that should be considered. The context includes the external business environment, strategy, culture, organizational complexity and stakeholder expectations. For a business facing a changing competitive landscape, getting the strategy right may be the main business challenge that a new leader will need to address. Culture may be the primary business challenge for an organization that faces a war for talent and needs to improve employee engagement and loyalty. Only after carefully defining the business challenge, including the underlying conditions in which executives will have to lead, is it possible to understand what kind of leader is needed. Clearly, boards are responsible for leading this process, which serves as a basis for assessing CEO search or succession candidates.

Consider the context. Success in one situation does not necessarily translate into success in another context. That’s why it’s important for boards to look deeper into CEO candidates’ experience to understand how the circumstances in which they were successful correlate to what is needed in the current situation. The objectives for the role — whether the CEO needs to lead a turnaround, for example — represent just part of the context that should be considered. The context includes the external business environment, strategy, culture, organizational complexity and stakeholder expectations. For a business facing a changing competitive landscape, getting the strategy right may be the main business challenge that a new leader will need to address. Culture may be the primary business challenge for an organization that faces a war for talent and needs to improve employee engagement and loyalty. Only after carefully defining the business challenge, including the underlying conditions in which executives will have to lead, is it possible to understand what kind of leader is needed. Clearly, boards are responsible for leading this process, which serves as a basis for assessing CEO search or succession candidates.

Watch your biases and assumptions. Making assumptions about an individual’s capabilities based on their experience or treating past experiences as a proxy for success can lead boards astray. We know of one example in which the board selected a fellow director as CEO in part because directors were hoping for more transparency and openness in the board/CEO relationship. Despite the CEO’s past experience as a board director, he struggled to build a transparent, open relationship with the board. Boards should be explicit about why specific experience or capabilities are important and assess candidates against them. They also should assess executives’ capacity to stretch, learn and adapt to new challenges and environments, which is important whether the person has prior CEO experience or is making the leap into the CEO role for the first time.

Watch your biases and assumptions. Making assumptions about an individual’s capabilities based on their experience or treating past experiences as a proxy for success can lead boards astray. We know of one example in which the board selected a fellow director as CEO in part because directors were hoping for more transparency and openness in the board/CEO relationship. Despite the CEO’s past experience as a board director, he struggled to build a transparent, open relationship with the board. Boards should be explicit about why specific experience or capabilities are important and assess candidates against them. They also should assess executives’ capacity to stretch, learn and adapt to new challenges and environments, which is important whether the person has prior CEO experience or is making the leap into the CEO role for the first time.

Understand candidates’ drive and motivation. The job of CEO is difficult, and becoming more challenging all the time. Some CEOs might take another CEO position assuming it will be easier the second time, but our research indicates that there is no reason to believe this is true. Every role is different, and the CEO has to be prepared to be a beginner again, in mindset and energy. Even when a CEO has led an organization with similar business challenges under similar circumstances, boards will want to consider whether the person has the energy and motivation for the new role, and for what period of time. Do they have a compelling vision for the new business? Are their personal circumstances now the same or different? Are they as ambitious as they were?

Understand candidates’ drive and motivation. The job of CEO is difficult, and becoming more challenging all the time. Some CEOs might take another CEO position assuming it will be easier the second time, but our research indicates that there is no reason to believe this is true. Every role is different, and the CEO has to be prepared to be a beginner again, in mindset and energy. Even when a CEO has led an organization with similar business challenges under similar circumstances, boards will want to consider whether the person has the energy and motivation for the new role, and for what period of time. Do they have a compelling vision for the new business? Are their personal circumstances now the same or different? Are they as ambitious as they were?

Conclusion

CEOs today are more likely than in the past to have prior CEO or board experience. It’s natural that boards would see value in these experiences, especially in giving CEOs an edge in communicating with the board, understanding board governance, managing risk and recognizing patterns. Our analysis of 736 complete CEO tenures, however, has found no correlation between previous CEO experience and shareholder value creation. This suggests that boards must carefully define the context in which the CEO will operate and articulate the specific capabilities, experience and leadership style required for success. What is more, they need to understand a candidate’s capacity to stretch, learn and adapt, and their energy and motivation. From there, they can consider how individuals’ prior experience can be specifically leveraged to address unique challenges for the role.